In 1316, several experienced master builders were summoned to the construction site in Chartres at the request of the cathedral chapter. They came from Paris. Serious incidents had recently occurred, although the edifice had been completed barely seventy-five years earlier. From the description of the observed “disorders,” it is easy to understand why the canons became alarmed and decided to seek the best advice, fearing that the situation might deteriorate further. In fact, the structural defects (rare as they are) known today had already begun to manifest in the decades following the construction of the Gothic cathedral.

What remains is an extraordinary document because it analyzes all the “weak points” of the edifice. Furthermore, it immerses us in the reality of a medieval construction site at the decision-making level: discussions among specialists, on-site observations, and visit reports. Although the terms of these reports may initially seem rather naive, they are, in fact, based on immediate insights of remarkable technical precision.

We are publishing this text from the chapter archives for the first time since 1900, when it appeared in the annals of the French Archaeological Congress. Until now, certain passages of the document had not been fully understood, but recent renovation work has clarified their references. As a result, several of the comments included here are entirely new.

Flying Buttresses and Columns of the Narthex

« + Item, nous avons veu les arz bouterez (1) qui espaulent (2) les voustes : ils faillent bien à jointeer (3) et recercher, et qui ne le fera briefment, il y porra bien avoir grant domage. »

(+ Item, we saw the flying buttresses (1) that support (2) the vaults: they require careful jointing (3) and repair, and if this is not done promptly, there could be significant damage.)

(1) The term flying buttress was already used by Villard de Honnecourt, under the spelling ars boterés. Regarding Notre-Dame of Cambrai, he writes: « avant en cest livre en trouverés les montées dedens et dehors, et lote le manière des capeles et des plains pans autresi et li manière des ars boterés ». (PI. XXVII, p. 117 et suiv.)

(“earlier in this book, you will find the elevations inside and out, and the entire layout of the chapels and flat sections as well as the arrangement of the ars boterés.” (PI. XXVII, p. 117 and following).

The analysis of the role played by flying buttresses —particularly the evolution of construction techniques— has been completely transformed since Mortet published this text in 1900.

Viollet-le-Duc’s considerations have left only three evident facts: the exceptional width of the nave (over 16 meters from the center of the piers), the considerable —yet variable— thickness of the vaults, and finally, the weight of the material. The oblique thrusts are more significant here than in any other cathedral.

It has been observed, at the level of the nave, that the highest of the arches was constructed a posteriori. It rests on the mass of the buttress and acts at the level of the upper cornice. The two junction points suggest it is an addition: the arch grafts onto a pyramidion that became redundant at the top of the buttress and conceals a foliage decoration beneath the circulation balustrade. Mortet was convinced this addition resulted from the 1316 inspection. However, the text makes no mention of such an addition and does not raise any structural defect.

A scholarly consensus dates this adjustment to the 13th century. It was carried out during the construction process: before or during the masonry work on the vaults, or at the very latest, in the years following their completion. Otherwise, the walls would not have been able to withstand the thrusts.

(2) One of the earliest examples of this verb (to support), as Mortet had already noted. See also the noun espauler in the sense of a piece of wood used as a support (Charter of 1248, in d’Herbomez: Et. sur le dial. du Tournaisis, p. 39).

(3) The words jointoyer and rejointoyer —referring to repairing the joints of an old masonry where they have deteriorated— are still used today in the language of masons. It is important to note how susceptible flying buttresses, exposed to weathering, are to such degradation. Some have already been repointed twice during the 20th century, while regular weed removal must be conducted by the Departmental Architecture and Heritage Service, with maintenance every three years.

« + Item, il y a II pilliers qui espaulent les tours, (1) où il faut bien amendement. (2) »

(+ Item, there are two pillars that support the towers (1), which are in need of proper repairs. (2)

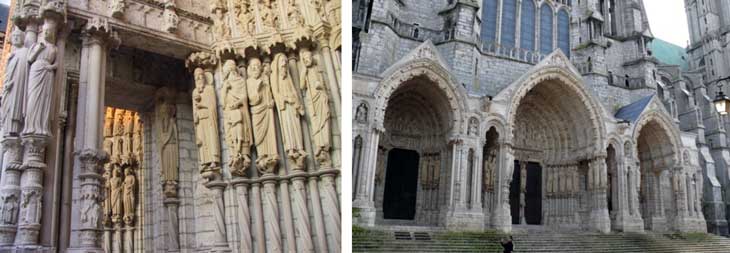

(1) Two pillars of the narthex. This cannot refer to the external buttresses; otherwise, the experts would have been curiously vague. It is most likely necessary to interpret pillar in the same sense as in the assessment of the crossing, suggesting that these are interior elements —two symmetrical pillars at the level of the towers.

(2) This paragraph has so far attracted no author’s attention, likely due to the difficulty of identifying the problem. From our perspective, there is no doubt that this section of the report pertains to the two columns in the narthex, which were integrated into the masonry of the towers during the construction of the nave in the early 13th century. It has long been observed that these columns were partially dismantled, giving this area a peculiar “stalactite” appearance. Indeed, masons removed the attached drums, leaving only those embedded in the thickness of the wall. Perhaps this decision was taken as early as the 14th century, as a precaution against the risk posed by falling stones.

In reality, each of the two Romanesque towers represents a cohesive block, independent of the nave and subject to shifts depending on soil density or temporary effects of drought —sometimes by more than a centimeter. The ribbed vaults stretched between these two masses have always shown structural vulnerabilities.

North and South Porches

« + Item, il faut bien meitre amendement es pilliers des galeries des portauz, (1) et convient faire en chascune béee (2) un ait (3) pour porter ce qui est desus: et mouvra (4) l’une des jambes desus le souz bassement, par dehors sus le pillier cornier (5), et l’autre jambe mouvra desus une reprise dou cors de l’iglise (6); et sera cel ait à toute sa boice (7), pour mains bouter, et sera ce fet par tous les liens (8) que l’en verra qu’il sera mestier. »

(+ Item, it is necessary to make proper repairs to the pillars of the gallery porches (1). It is also essential to construct in each bay (2) an arch (3) to support what lies above. One of the legs (4) will rest on the outer base above the corner pillar (5), while the other leg will rest on an extension of the church structure (6). This arch will need to be fully built out (7) to provide better support, and this should be done with all the necessary reinforcements (8) wherever deemed necessary.)

« + Item, (9) il faut es portauz devant: les couvertures sont routes et dépecées, pour quoi il seroit bon qu’en meist en chascune (10) un tirant de fer, pour les aider à soustenir, et seroit bien seanz pour oster le péril. »

(+ Item, (9) repairs are needed at the front porches: the coverings are rotted and damaged, so it would be wise to place in each one (10) an iron tie-rod to help support them, which would greatly reduce the risk of collapse.)

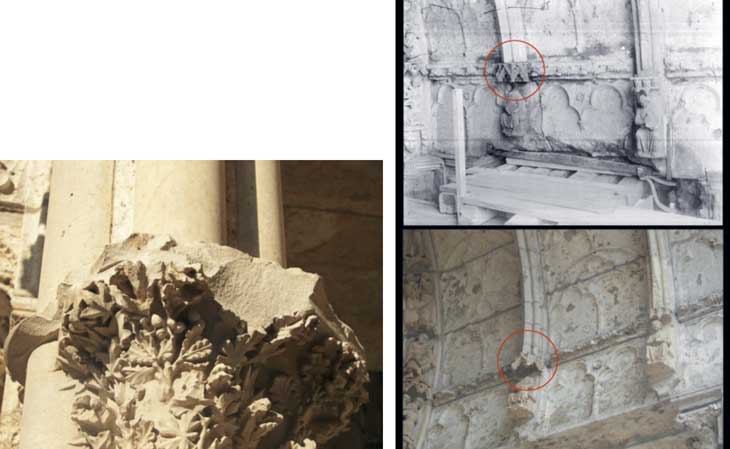

(1) North and South Porches. Among the pillars mentioned in the report, one stands out due to its distinctive stylistic features from the early 14th century, adorned with exceptionally fine foliage. This is one of the supports to the left of the central bay of the north porch, where David’s battle with Goliath is depicted on the pedestal. Should we assume that this pillar was severely fractured and had to be entirely replaced, while the others could still be repaired identically?

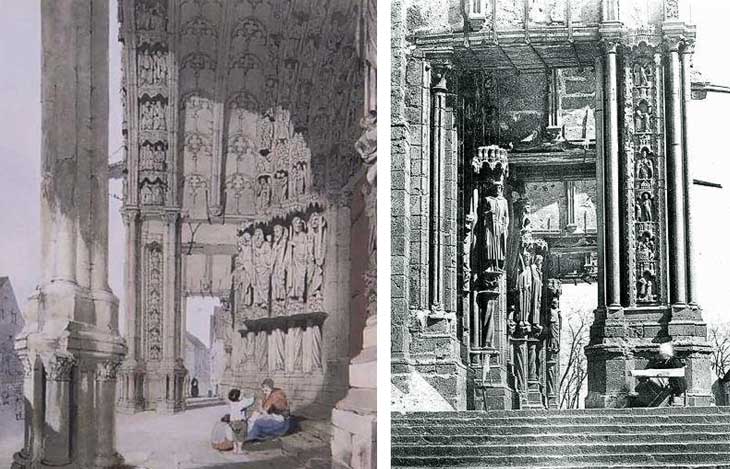

A small canopy was also replaced in the 14th century in one of the most affected areas of the north portal —at the junctions of the archivolts (right bay). The restorers of the 1900s overlooked this. When they replaced the lintel, they “aligned” this canopy with its neighbor.

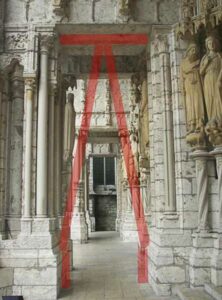

(2) The “bays” likely refer to the lateral openings between the porches, passing beneath massive lintels that support the outer archivolts. These bays allow for free movement under the projecting structures. This is probably the axis of displacement referred to in the text as the “galleries.”

The primary structural issues stemmed from a severe design flaw —likely due to negligence or overconfidence on the part of one or more master builders. The four powerful buttresses on the facades of the transepts and lateral towers generate significant forces. These forces act vertically, albeit slightly outward. However, the buttresses extend nearly a meter beyond the openings between the porches, directly weighing on the lintels mentioned earlier, which are incapable of withstanding such pressure.

(3) The term “ait” (barely legible in the original document) presents significant challenges, and none of the philological solutions proposed are entirely satisfactory. To understand the report’s subject, one must first determine its objectives and methods.

In fact, the description of the aits, struts, and other wooden structures is not that of a permanent arrangement but of a temporary support system, allowing for the replacement of defective piers supporting the porch.

This means that individual elements could be removed without causing the entire porch to collapse.

The report thus refers to beam arrangements rather than masonry supports.

This was identified by M. Jusselin, who interpreted the term lien (“link”) as commonly used in carpentry.

The final part of this paragraph specifies the placement of these temporary supports. The choice of anchoring points and areas to reinforce is crucial.

(4) “Mouvra” does not imply that the structures were designed to move. The verb should be understood as: “will be put in place…”

(5) This refers to an angle pillar, one that forms a corner. More broadly, a corner pier designates any pillar supporting a porch, particularly in covered arcades.

(6) It is clear that the discussion revolves around supporting the lintels. No author has yet understood the mechanism as described in the report. Most likely, this “jambe desus une reprise du cors de l’iglise” (“leg above a continuation of the church body”) refers to a diagonal beam anchored to the base of the transept wall, where a “plinth” could indeed secure it. One can imagine one leg placed on this side, “inward,” while the other would rest “outward” on the “souz bassement’” (“base”) of the “pillier cornier’” (“corner pillar.”) That is, a second diagonal beam would rest on one of the masses supporting the forward piers, which also features elements capable of securing it —both beams locking into place at the top where they support the lintel.

(6) It is clear that the discussion revolves around supporting the lintels. No author has yet understood the mechanism as described in the report. Most likely, this “jambe desus une reprise du cors de l’iglise” (“leg above a continuation of the church body”) refers to a diagonal beam anchored to the base of the transept wall, where a “plinth” could indeed secure it. One can imagine one leg placed on this side, “inward,” while the other would rest “outward” on the “souz bassement’” (“base”) of the “pillier cornier’” (“corner pillar.”) That is, a second diagonal beam would rest on one of the masses supporting the forward piers, which also features elements capable of securing it —both beams locking into place at the top where they support the lintel.

(7) In some timber-framed buildings, boise refers to a reinforced post, such as a corbel console extending to the ground. Such reinforcements would alleviate the ait, making the pressure more bearable: “pour moins bouter” (“to reduce stress.”) We propose the following interpretation, which seems to render the text accurately. As the diagonal “legs” rested on the bases of the forward piers on one side and the wall base on the other, a vertical piece could prevent them from sliding downward. This arrangement made the structure nearly indestructible, except if one of the legs yielded under pressure.

(8) ‘Tous les liens que l’en verra qu’il sera mestier’:

(“All the links that will be seen as necessary”.) In addition to the elements already mentioned, additional tie beams were planned to strengthen the main beams.

(9) This paragraph appears later in the report, just before addressing the scaffolding for the crossing and the state of the wooden framework. It explicitly mentions metal supports, which the previous paragraph omits, while both analyze the same “defects.” This suggests two distinct phases. After mitigating the most immediate danger—the collapse of porch-supporting columns, likely too light in design and possibly cracked—it became necessary to address the medium-term issue of the transverse lintels. These supported the porch’s archivolts and showed persistent signs of weakness.

Metal reinforcements, visible in old engravings or photographs, were installed until the restorations by architect Selmersheim (around 1895 for the south porch, 1905 for the north porch). The arrangement was similar for all twelve bays (six north, six south). Iron bars were placed above the lintels and embedded into the transept masonry. Additional bars were installed below, sometimes resting on consoles sealed into the piers. Clamps secured the lintels at regular intervals to prevent failure.

Around 1900, the decision was made to emulate the 14th-century model. The archivolts were redirected onto steel beams embedded in cement.

(10) Likely an elliptical reasoning. To clarify, interpret as: “on each of the lateral supports on which these coverings rest.”

Next part and conclusion: Expert Report – North and South Porches, Spire, and Roof.