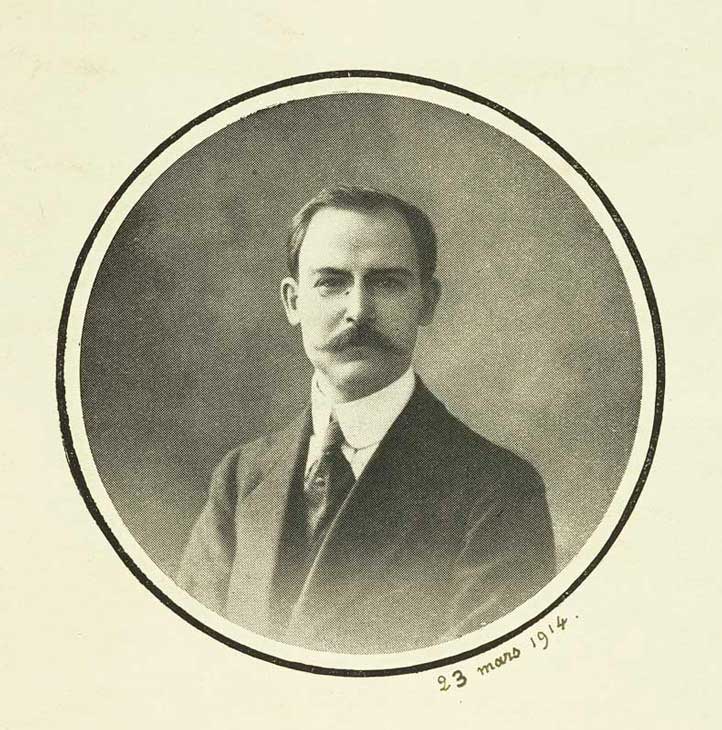

Maurice JUSSELIN, eminent paleographer and great specialist in Tironian notes, could have become a renowned professor. Archivist for the Eure et Loir department and president of the Eure et Loir archaeological society, he finally turned his attention to the Chartrain region. He is the author of a large number of opuscules on the subject, too little known, but always perfectly documented. In fact, his bibliography is several pages long. For he has devoted himself entirely to his work, gathering and annotating precious documents, and devoting to his studies an erudition that never fails to amaze – his ‘footnotes’ sometimes taking up the bulk of the subject. He is known to be impartial and concerned only with the truth. Nothing is as interesting as his enlightened comments on the texts that make up Chartres Cathedral’s ‘legendary collection’.

“When a tradition is long-lived, it is reported in precise terms and without comment, and very often there is no need to recount it in texts. As the centuries go by, memories fade, and successive generations feel the need not only to safeguard the tradition threatened by oblivion by talking about it at greater length, but also to add useless commentaries that are apt to transform a truth into a legend. The traditions of the Chartres church have suffered vicissitudes of this nature. We have preserved no figurative or written monuments from the early centuries, but when texts appear at the end of the 13th century that might contain precious testimonies, they are extremely brief. In every archive, we read the simple statement that the church of Chartres was founded in honor of the Virgin Mary, and that the most venerated of the relics preserved there is the Veil of the Blessed Virgin; further details were unnecessary, there was no need to ask the question.

At the beginning of the 14th century, French historiography underwent profound changes, and difficulties forced the Chartres church to defend its centuries-old rights. The terms became clearer. The libri antiqui ecclesie, old texts now unfortunately lost, were invoked in favor of Tradition, but their existence was proven by a summary inventory drawn up by a canon in the mid-sixteenth century.

The year 1322 saw the appearance of a document of impressive scope. The chapters of most of the churches in France wrote to Pope John XXII on behalf of the Chartres canons, all of whom would have been well advised to claim the highest antiquity for their own church, but they nonetheless proclaimed without hesitation that the Virgin Mary, during her lifetime, had chosen the church of Chartres as her temple: Cum Virgo beatissima Dei mater venerabile sibi templum, dum vitam duceret in humanis, elegerit ecclesiam Carnotensem.

In September 1330, the Count of Dreux recalled that the venerable church of Chartres had been founded in honor of the Blessed Virgin Mary before the Assumption: antequam Celos ascenderet. The following year, in April 1331, the same lord affirmed his devotion to this church founded during the Virgin’s lifetime. In 1356, an act of King Jean le Bon stated that the foundation of the church, dating back to the earliest antiquity, had taken place during the Virgin’s lifetime, as written in the ancient books of the said church, and that the Virgin had made this church her favorite abode, as witnessed by the many miracles she performed there. Charles V, successor to John II, also said in 1367 that the foundation had taken place during the Virgin’s lifetime, and added that the testimony of certain ancient and authentic writings was corroborated by the popular voice, i.e. by tradition. Finally, in 1388, Pierre de Craon also acknowledges that the church was founded during the Virgin’s lifetime, “et Elle estant en Terre (sainte) avecques les Saints Apôtres au temps de l’Ascension de Nostre Seigneur“.

As this text no longer refers to the Assumption, a number of uncertainties were beginning to creep in, not with regard to Tradition itself, but to the circumstances surrounding it.

Bishop Jean Lefèvre, to whom the destinies of the Chartres diocese were entrusted at the time, understood with remarkable foresight that the time had come to fix both history and tradition. In 1389, this prelate entrusted one of his clerics with the task of writing the compilation we call the Old Chronicle. The work had a sacred character, and was transcribed onto the manuscript after the leaves on which we read the Miracles of Notre-Dame, and before those on which we read the text of an obituary. It had its place among the ancient texts, the libri antiqui ecclesie spoken of by the kings of France and all the charters, and represented for contemporaries the Tradition and history of the Church of Chartres in their most definitive form.

The chronicler tells us that the church was founded before the birth of Christ, that it was dedicated to the Virgin who was to give birth, Virgo paritura, by the first inhabitants who believed in the coming of Christ from a Virgin; that a prince of the Chartres region, approving this foundation, had a statue made of a Virgin carrying a child in her lap, which was venerated in a secret place alongside the idols, and that the pontiffs of the idols presided over the new cult. In the second part, devoted to the history of the bishops, the author states that the foundation took place not during the Virgin’s lifetime, as previous texts asserted, but before her birth. This opinion, undoubtedly drawn from an ancient testimony, and also expressed with the intention of fortifying Tradition, of better highlighting its prophetic character, of making pagan history a figure of Christian history, will henceforth tend to prevail”.