by Félicité Schuler-Lagier, Interpreter and Lecturer at the Centre international du Vitrail

courtesy of Chartres Sanctuaire du Monde

The images of working the land (sowing, harvesting, grape-gathering), particularly in calendars, are a reminder that the Church gave pride of place to the ancient work of the soil, ploughing having been imposed on man by God himself (Gn 2:15). The products of this work, wine and bread, are even sanctified, since they are used in the Church.

Peasants, winegrowers and bakers were among the trades considered lawful and praiseworthy in medieval society.

“Legitimate” and “illegitimate” trades

Fig. 1 : Winemakers picking the clusters and crushing the grapes during the harvest, detail stained glass 28a.

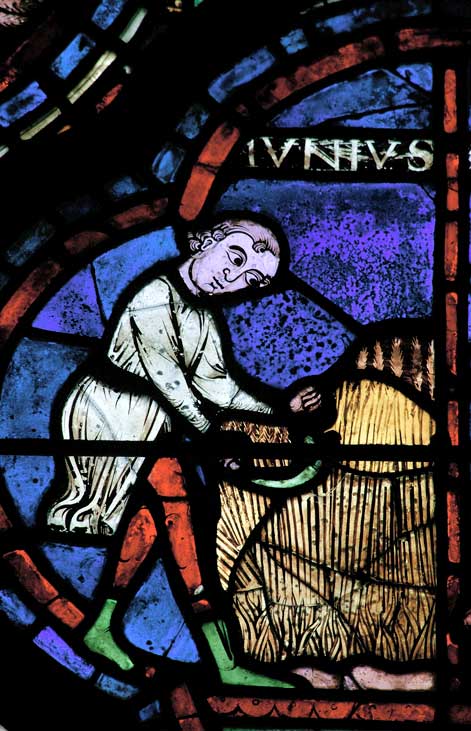

Fig. 2 : The wheat harvest, detail of stained glass 28a.

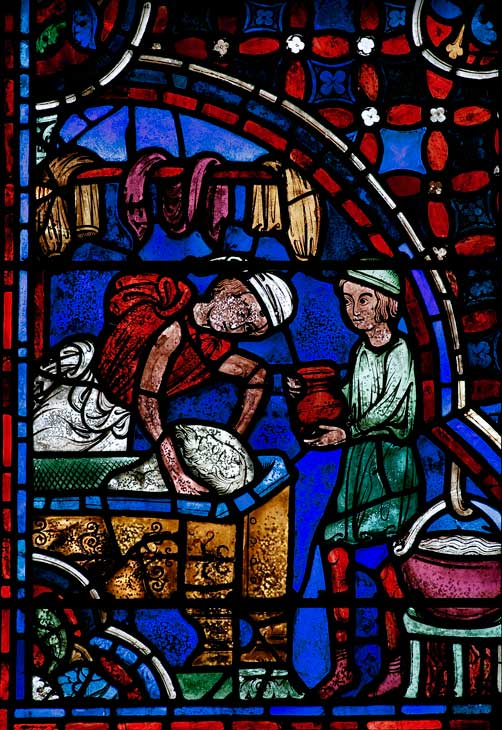

Fig. 3 : Master baker, preparing the dough for the Eucharistic bread, a servant brings him the water, detail from stained glass 00.

Fig. 4 : In the dough intended for the making of the Eucharistic bread, the face of Christ appears. Remarkably, the kneading trough combines the two colors gold and blue, which herald a miracle of healing or resurrection in the stained glass windows of Chartres, while the baker, dressed in red and white, wears the two colors prescribed for Christ in a medieval manuscript of the liturgical drama of the Pilgrims of Emmaus, in the scene where he appears to his disciples, stained glass detail 00.

Fig. 5 : Melchizedek’s Bread, detail from the lancet of the north portal.

Fig. 6 : Ten perfectly round loaves of bread are depicted in this basket carried by two men using a green stick passed through two handles. The two carriers lean their right hands on a white stick, a pilgrim’s attribute; the burden is heavy, and the path seems long, rocky, and difficult, detail from stained glass 100.

The loaves in a basket still evoke the Manna (Exodus 16:4), that miraculous bread which nourished the Hebrews during their long journey through the desert, heavenly and supernatural bread that only lasted for a day. In the Temple, there were also loaves on the table of the showbread (Exodus 25:23), another prefiguration of the Eucharistic bread. Every basket overflowing with loaves also recalls the miracles of the multiplication of loaves performed by Jesus. Was it not necessary to gather seven large baskets to collect the leftover bread after the crowd had been satisfied?

Fig. 7 : Scene taking place in the bakery shop. A basket containing five loaves alludes to the five loaves with which Jesus fed his disciples and the crowd (Mt 14:19). Seven other loaves arranged on the counter recall another multiplication of loaves (Mt 15:36) where Jesus fed the people with seven loaves, detail stained glass 00.

The immense bread baskets at the bottom of the two large lancets of the choir, which the faithful in the Middle Ages could easily spot despite the presence of the rood screen, also recall a very ancient tradition, that of blessed bread. Since antiquity, it became customary to bless at Mass the bread offered by the faithful that had not been consecrated and to distribute it to the people at the end of Mass. These blessed breads, or eulogies, were also sent as a sign of charity between parishes. Many Lives of saints recount the miracles performed by the eulogies. In the Middle Ages, the blessed breads were wrapped in white cloths or in silk fabric and carried in baskets, artistically woven wicker objects, closed for transport over long distances, and opened for distribution in the church. Saint Gregory of Nazianzus speaks of a basket (canistrum) filled with the purest wheat bread upon which he offered prayers and made the sign of the cross.

Fig. 8 : Distribution of blessed bread, detail stained glass 102.

To be continued…

Original article published in the Lettre de Chartres Sanctuaire du Monde (December 2021)