Georges Goyau, the great historian and essayist, member of the Académie Française, was invited to the Marian celebrations in 1927 to speak about the role played by Chartres in Marian spirituality. “It is appropriate that religious history […] should research and grasp, eight and nine centuries back, the influence of Chartres’ initiatives on the Church of France and on Christianity.”

On this occasion, he emphasized the considerable impact of Fulbert’s works.

© Meurisse press agency

It was almost nine hundred years ago that Fulbert, bishop of Chartres, followed by his works or, to put it better, preceded by them, gave his ardent soul back to God. One of his disciples, Sigon, took the Martyrologe of the Chartres church and opened it, on April 10, the day of Fulbert’s death; he inserted in a few verses the eulogy of the deceased, « illustrious light given by God to the world ».

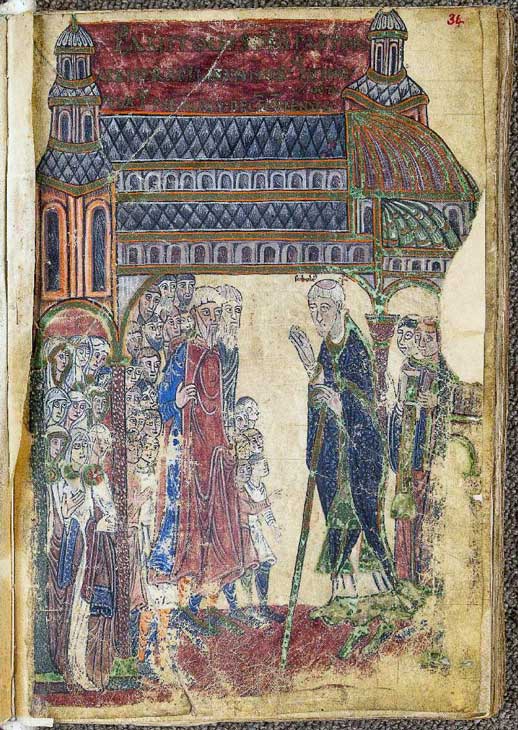

Then, in the same place in the book, the miniaturist André de Micy introduced a sumptuous image. It showed a priest preaching, with two deacons behind him: one of his hands was raised, initiating or completing an oratorical gesture; the other hand was resting on a crozier. An inscription named the figure Fulbert: « twenty-one years and six months, » it said, « he was the shepherd of the Lord’s sheep ».

In front of him were a number of young clerics, the town’s burghers in their Sunday best, dressed in richly colored tunics; women, finally, uniformly draped in long cloaks that covered their heads, cloaks of a white color tending to blue, and these women could only be distinguished from one another by the opulence or sobriety of the clasps, which closed these cloaks.

Fulbert in Chartres Cathedral © Municipal library, Ms. 4, fol. 94

André de Micy was drawing the southern façade of Fulbert’s basilica from the ridge upwards, a task in which he showed great concern for accuracy. The eleven windows that still light the way when we visit today’s crypt are punctually aligned in André de Micy’s design. We have before our eyes the cathedral of the time, freshly rebuilt in the wake of the fire of 1020; and the Chartrains of the time, as Sigon and André de Micy could observe them in the sacred liturgies; and Fulbert himself, fulfilling his office as doctor of the faith. This cathedral, where his voice had just fallen but his ardour had never faded, remained full of his memory.

In his shadow, he had once taught at the Chartres schools, whose philosophical and literary glory preceded that of the University of Paris. To raise the basilica from its ashes, he had appealed to Robert the Pious, King of France; to William V, Duke of Aquitaine; to Canute the Great, King of England, Denmark, Sweden and Norway: the rebuilt cathedral appeared in all truth as the daughter of his soul, the fruit of his life. But once Fulbert was dead, the doors of the edifice closed on his corpse. Cathedrals, however, are generally ossuaries, and house bishops and canons, kings and queens, and distinguished benefactors until the day of final judgment. But in the Chartres ossuary, no son of Eve, even if he were a bishop, was allowed to sleep his last sleep; the only privilege in this respect was for the martyrs who, deep in the well of the Saints Forts, await the glorious resurrection of their once-scarred flesh. Fulbert’s remains would have seemed an intruder in the monument of which he was the architect. The very special lordship that Chartres piety recognized in the Virgin Mary did not include abandoning the slightest inch of the earth to human bones. In Chartres, the word Notre-Dame, Nostra Domina, seemed to have a more rigorous, more juridical, I was going to say more feudal, meaning than anywhere else. Mary, on this hill, was truly the sovereign, and an English monk of the 12th century wrote in a collection of miracles: « The city of Chartres is so fervent in the worship of Mary that if anyone, even a simple man of the people, confined himself to calling her Sainte Marie without attaching the title of Notre-Dame, he would be accused of a capital crime, and everyone would point the finger at him ».

A Chartrain worthy of the name, therefore, invoked the Virgin by her title as well as her name, and called her Notre-Dame Sainte-Marie, thus paying homage to both her earthly supremacy and her heavenly glory. A few letters addressed to Fulbert by his disciple Hildegaire are touching proof of the place this Lady occupied in the life of a Chartrain man.

Fulbert was delighted to accept the position of treasurer of Saint-Hilaire in Poitiers, where he hoped to find resources for the construction of Chartres cathedral. Around 1204, he delegated Hildegaire to take charge of the treasury. Hildegaire, in faraway Poitiers, soon began to feel homesick, and in a few precise strokes could be seen to diagnose his malaise. He missed Chartres because of Fulbert, he missed it because of the Virgin. « I confess to you that it is very painful for me, who am so uneducated and who need your lessons every day, to have been deprived for so long of your presence and prevented from paying my respects to the Blessed Virgin… If only I were sure that you would soon do the church of Saint-Hilaire the honor of visiting it! This hope would make it bearable for me to remain so far away from your entourage and the service of Notre-Dame ».

A year passed, and Hildegaire returned to the charge. « No, I can endure no more, except that your orders force me to, and my exile, and the too long impotence where I am to render my duties to the Mother of God and to you ».

Finally Fulbert recalled Hildegaire, who wrote to the dean who had temporarily succeeded him in the treasury: « I am so attached to the service of Saint Mary that I cannot remain absent from it without fault and without damage. The eminent Mother of God will plead my case with Saint Hilaire, if I have offended this saint; certainly I would never have preferred a lesser saint to Saint Hilaire. But I had to return to the clientele of the Mother of the Lord, who is justly elevated above all the archangels, I who am her tiny infant ».