How did Étienne Houvet become a photographer and publisher?

From the publication “Étienne and Marie Houvet, Chantres de Notre-Dame”.

Thanks to Étienne Houvet’s photographs, we’re able to discover in detail the sculptures of Chartres Cathedral, a privilege previously reserved for swallows, as Émile Mâle so picturesquely wrote.

Étienne Houvet was born on June 18, 1868 in the village of Cercottes, a few kilometers north of Orléans. The Houvet parents and their two sons (Joseph, the eldest, and Étienne, four years his junior) arrived in La Bazoche-Gouet, in the Perche region, around 1870. They ran a grocery and haberdashery business in the Grande Rue. In 1881, Nicolas, the father, was registered as a cloth merchant. The two brothers worked with their parents; Étienne did the rounds in the countryside, an unprofitable job.

Étienne Houvet was born on June 18, 1868 in the village of Cercottes, a few kilometers north of Orléans. The Houvet parents and their two sons (Joseph, the eldest, and Étienne, four years his junior) arrived in La Bazoche-Gouet, in the Perche region, around 1870. They ran a grocery and haberdashery business in the Grande Rue. In 1881, Nicolas, the father, was registered as a cloth merchant. The two brothers worked with their parents; Étienne did the rounds in the countryside, an unprofitable job.

In 1897, he arrived at Chartres Cathedral; initially a servant in the master’s office, in charge of crypt maintenance, he became sacristan of the upper church in 1906.

From liturgy, he took an interest in the architecture of the building and became its janitor.

Without attending school, he studied art history and took up photography.

His interpretation of religious sculpture was facilitated by a religious feeling that had led him to consider monastic life a few years earlier. He benefited from the publications of such classics as Émile Mâle, Camille Enlart and Henri Focillon.

His master in photography was Canon Delaporte, who had been familiar with the discipline from an early age. Around 1910, Étienne Houvet began to take photographs without a camera, producing his first reproductions using slow-printing sensitive paper. He was particularly successful with an image of the Virgin Mary with the Infant Jesus, from the grisailles of the Saint-Piat chapel. This was the souvenir image he produced for his jubilee of service at the cathedral in 1947.

Later, he used a friend’s camera. It wasn’t until 1914 that he acquired a 13 x 18 camera. Gradually, with the proceeds from the sale of his first works, he was able to add to his equipment, in particular an 18 x 24 camera, the format of the album plates, then a 24 x 30.

Shooting was done using rolling scaffolding and a double ladder to minimize distortion. An artist must also take into account the time of day, and observe the play of light and shadow that can give a certain relief or vigor of expression to a physiognomy. The photographer must aim for a faithful image of the work to be reproduced; opting for a personal interpretation may result in a distortion of the work, or even a betrayal.

After publishing a number of documents, Étienne Houvet decided to work methodically, resulting in a first album of 96 plates, devoted to the “Portail royal”. No publisher was willing to commit to this perilous operation.

So he embarked on a real adventure himself. In 1919, he published on his own account. To pay the printer, Faucheux, in Chelles, he had to take out a loan, secured by his own house.

The success surpassed all expectations; the work, honored with a preface by Émile Mâle, sold very well and allowed him to repay the loan of 7000 francs.

This made him bold. Despite suffering from pleurisy during the summer, he began work on two new albums devoted to the north portal, which where published in January 1920. They present the history of the world from its creation to the death of the Virgin Mary. It was this portal that our photographer was particularly fond of, for all its symbolism: the figuration of creation, the ascetic figure of John the Baptist inviting conversion, the realities of daily life in the work of the months.

In the same year, he published two other albums featuring the south portal, that of the New Covenant: Christ in the midst of his apostles, escorted by the martyrs on his right and the confessors on his left.

The year 1920 was very tough: poor health and the moral anguish caused by a new 20,000 francs loan put our man to a severe test.

Fortunately, the success of Le portail royal brought renewed success for the four new volumes.

After some dark days, Houvet saw himself saved.

In 1921, he delivered an album on architecture and, despite his lack of interest in the Renaissance, another on the choir’s enclosure scenes, and we are grateful to him – along with Émile Mâle – for having given us with this publication a history lesson on the transformation of French sculpture.

An anecdote about Étienne Houvet’s relationship with Émile Mâle is worth mentioning here. The latter had just published his work on religious art in 13th-century France; he had made an error of interpretation on the iconography of Christ’s temptations. He happened to come to Chartres and joined a group of visitors; he followed the explanations of Étienne Houvet, who was quick to point out Émile Mâle’s mistake. When the visit was over, Émile Mâle, without making himself known, came to the guide to ask for explanations. Playing a bit of a provocateur, he asked what he was basing his protest on. Étienne Houvet replied quite simply that he had merely reread the Gospel. The great professor congratulated him and offered him the book, which was beyond the means of our Chartrain guide.

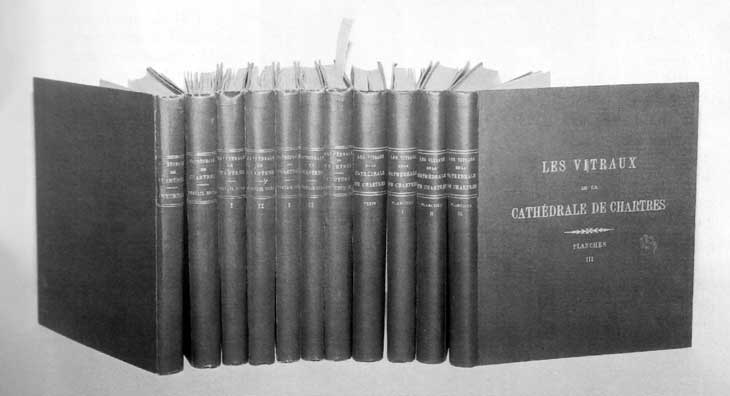

The three albums devoted to the stained glass windows have a special history. They are partly linked to the events of the Great War of 1914-1918. The story was told by Canon Yves Delaporte in his masterly book Les vitraux de la cathédrale de Chartres, 1926. In May 1918, the Ministère des Beaux-arts ordered the immediate removal and safekeeping of the ancient stained-glass windows. The Archaeological Society, in a board meeting on May 23 and a general assembly two days later, decided to have photographs taken of all the stained-glass windows. The chosen operator was Mr. Houvet, “already known as a skilled photographer”. As scaffolding was required, the Society voted a sum of 500 francs. With removal to begin immediately, the scaffolding was ready for use on June 1.

By November 6, the removal was complete. The next day, we learned that the armistice had been called. Despite this news, the stained glass windows in the Saint-Piat chapel were removed during November. The removal was justified, as a string of bombs fell in the Maunoury-Reverdy neighborhood on August 15, 1918. During the work, Mr. Houvet was able to precede the glassmakers by working either on his scaffolding or from the triforiums. The result was a virtually complete collection of stained-glass reproductions. Although the photographs are sometimes mediocre, they are of great documentary interest. For publication, the stained glass shots from the 1918 campaign were supplemented by detailed shots taken in the workshops during the restoration work – which was not completed until 1924.

It is quite likely that some of the detail shots, interspersed among the overall plates, are the work of Canon Delaporte.

The two co-authors did not work at the same pace. It seems that Étienne Houvet was impatient to publish, while Canon Delaporte argued that writing could not be improvised. In his introduction to the re-edition of Le Portail royal in 1950, Delaporte states that the work on the stained-glass windows “bears the date 1926”, and we note that Émile Mâle’s acknowledgements are dated 1927.

The 943 photographic shots used for the ten albums of the monograph, printed in phototype, as well as many others used for separate plates, images, postcards and color prints on plastic, are now preserved in the Archives of the Chartres diocese.

To illustrate Étienne Houvet’s notoriety, I think it’s worth recalling the great solicitude – which may surprise us – shown by the Germans before they left our territory in 1944. A German general gave the order to recover “from the house of a Mr. Houvet, a very important collection of photographic plates of the cathedral… so that this artistic treasure would not fall into the hands of the Allies”.

The two LKW trucks tasked with this mission were unable to reach Chartres, as they were mauled by the merciless air force.

Chartres was luckier than Amiens, where M. Regnault, Étienne Houvet’s counterpart who had also collected a large number of photographs, saw them destroyed by bombing, and died of grief.

By the mid-twentieth century, it was widely acknowledged that there were three guides with a passion for their monument: Houvet in Chartres, Regnault in Amiens and Barbier in Saulieu.

Étienne Houvet, in addition to bearing witness to his faith, shared his admiration for the cathedral both in his guided tours and in the albums of his monograph, which have been placed on the shelves of major libraries.

Canon Pierre Bizeau †

Diocesan Archivist