… or ‘A long analysis of an almost insignificant detail’.

Taking the time to answer these questions means venturing into the world of the 13th century through ‘the very small end of the spyglass’: its aesthetic choices, its symbolic choices, its clever master glassmakers. Come along with us…

… continued

In the third circle, the problem is complicated by the fact that the Virgin’s tomb is supported by columns, a process that is both symbolic (the deceased raised to altar level) and descriptive (burials of princes and bishops – early 13th century). Now that the red dot has been rendered useless, the master glassmaker nevertheless persists – as if there were a deliberate desire to homogenize:

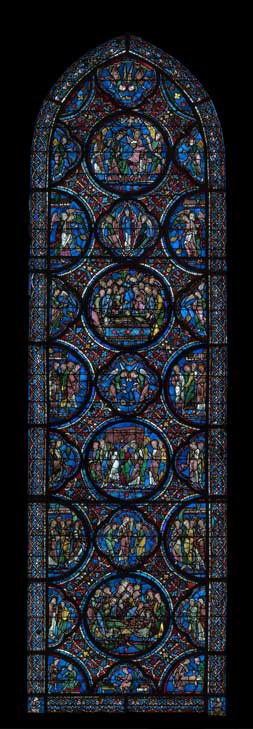

Entombment, glorification of the Virgin Mary ©NDChartres-fonds Gaud

Three red dots adorn the tomb, just a few centimetres above the ground. What’s astonishing, what makes us smile – and what testifies to a famous sense of opportunism – is that he follows a typical tomb formula, as seen on many other stained-glass windows. In fact, he makes only a secondary change, replacing the rosettes with plain dots (for comparison, see Saint Apollinaire, Saint Silvestre – where the colors are reversed: blue motif on red tomb). For the first time, what appeared to be an ornamental exception is ‘reintegrated’ into the functional.

In the fourth circle, the horizontal ground poses exactly the same problem as the second. Once again, the master glassworker chose to evolve and slightly modify the ‘point’ solution. He drew on existing models from other stained-glass windows, in particular the idea of an arcature, itself supporting a decorated line used as a floor (see Saint Nicolas – Chapel of the Confessors, Saint Thomas):

Coronation of the Virgin Mary, Glorification of the Virgin Mary stained glass window ©NDChartres-fonds Gaud

What the attentive observer will not fail to notice, and which should be highlighted with humor, is that the red lenses narrow towards the bottom, and ultimately appear as a sort of intermediary hesitating between the point and the arch. Again, we shouldn’t rule out the model provided by certain tombs – where this kind of arcade can be spotted (see Saint Stephen – with the same red/blue transposition), but the fact remains that this is an architectural support. And so, for a second time, the exception of the red dot is the object of a functional ‘catch-up’ – in extremis, one might say.

The whole point of this reflection is to follow the craftsman’s questioning step by step. On an admittedly secondary problem, we see him confronted with two mutually exclusive logics:

– on the one hand, a highly graphic vision of stained glass, with a concern for coherence between all the panels, for a guiding thread – dare we say a dotted red thread – according to a reasoning all the more valid as each scene extends, at the same level, over three panels ;

– on the other hand, a determination to conceive each scene as a realistic slice of life, with respect for the standard model proposed by the commissioners – and therefore an obligation to avoid digressions.

Better still, we understand his hesitations. We almost feel like smiling at him, eight hundred years on.

Could this be a sign of archaism in the Gothic cathedral? What do we see? Two ‘signs’ that could be understood as ‘outstretched fingers’, as a sovereign intervention of the craftsman in the narrative: “this is the scene you must look at before any other”. Then there are two tricks above, which we can’t deal with today without amusement, and which, for a time, complete the glass roof – with continuity in terms of form, but a renunciation of the idea of background: it’s no longer a question of an autonomous ‘sign’, outside the narrative, but only of adding to the veracity of the scene. Two signs, two tricks and then nothing more… except for the same dots that reappear when they come into contact with the ogival borders at the very top of the glass roof, along the edges of the pointed arch.

We’d be forgiven for thinking that this tiny detail is more important than it first appears – at least as a revelation. If we look at the underlying logic of Romanesque and Gothic art, one being as attached to the symbol as the other is to the real, it is perhaps at this precise moment that authentic ‘Romanesque art’ would discreetly give Chartres one of its very last breaths – one of its last fires, with the color of embers.

Glorification of the Virgin (south aisle) ©NDChartres-fonds Gaud