Beyond the bustle of the city and the passage of time, the Saint-Lubin crypt lies deep within the Notre-Dame de Chartres Cathedral, directly beneath the high altar of the upper church.

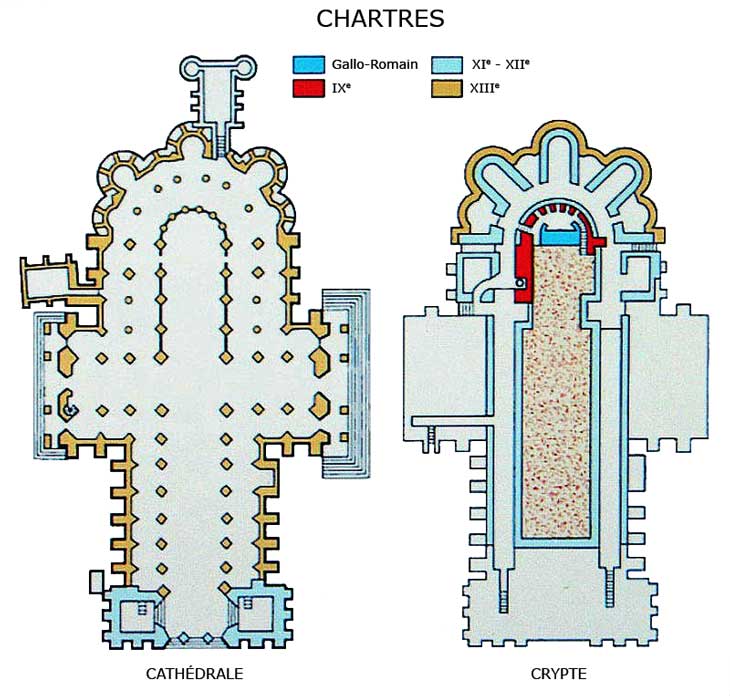

It is integrated into the U-shaped plan of the immense Fulbert crypt, completed in 1024. The term “Crypt” here primarily refers to a vaulted, secret, hidden space. It owes its name to Saint Lubin, a popular saint and bishop of Chartres in the 6th century (the only bishop to have his historiated stained glass window in the cathedral).

The era of Saint Lubin coincides with the completion of the evangelization of rural areas. He defined the boundaries of the diocese, which was one of the largest in France: that of Chartres, bordered to the north by the Seine, to the south nearly reaching the Cher, to the east extending to Étampes, and to the west beyond the sources of the Eure (before Le Mans).

Here, one suddenly plunges into a very ancient history, where we are confronted with the question of the origins of the cathedral.

In ancient times, Chartres was the capital of the Carnutes tribe, a Gallic people from whom the city derives its name (Chartres, from the Latin Autricum). They were the ones who founded the first village and the first town. The present-day landscape has changed little since then: the Carnutes were already cultivating cereals.

A significant city from the Gallo-Roman period, an ancient city built on the Eure River and radiating for dozens of kilometers around, Chartres was both a religious, political, and military capital.

At the beginning of the 20th century, René Merlet, curator of the departmental archives, undertook excavations in the cathedral’s underground. He questioned its successive constructions. His research identified elements from ancient, Merovingian, and Carolingian periods within the Saint-Lubin crypt. The precise dating of this site remains subject to various hypotheses: the first church would date back to the 4th century. The second would have been built before the year 1000. And the third, in turn, would have been constructed just before or in preparation for the Fulbert crypt (1024).

As early as the 4th century, we have the first mention of a bishop of Chartres: in 511, this bishop is historically attested by his participation in the Council of Orléans, where he is listed in the episcopal register. This first great council of the Frankish Church reflects Clovis’s intention to establish cordial relations between civil and religious authorities.

Crypt: clustered pillar, original floor © NDC

The current access to the Saint-Lubin crypt is located opposite the sacristy of the Fulbert crypt (Fulbert was a learned bishop of the early 11th century and founder of the School of Chartres), via a staircase pierced through the wall in the 18th century. During the entire period of the Romanesque cathedral (11th century), the only way to access it was through a trapdoor in the choir. Thus, the pilgrim descends into the oldest part, this vault buried deep within the cathedral. We are in “the Holy of Holies.”

At the foot of the staircase, there is a small trapdoor called the “cachette,” where the canons hid the most precious liturgical objects or relics to protect them when necessary.

The pilgrim then enters a semi-circular room called the martyrium. Modest in size, this room features a wall approximately three meters thick. Inside are five niches that allowed for the display of relics of sainted martyrs —hence its designation as a martyrium. In front, two free-standing, imposing rectangular pillars serve as powerful supports, bearing traces of earlier tools such as the polka at their base —indicating that they were likely built with repurposed stones. Facing these pillars is a straight wall enclosing this hemicycle vault, where alternating layers of bricks and flint rubble can be seen over several rows. It is of Gallo-Roman style. Just in front, a large semi-cylindrical column rises from the ground and expands into a round-arched vault. At its base, one can observe the original floor level of the previous cathedral, which is 1.65 meters lower. The current level would therefore have been established by Fulbert.

Crypt: clustered pillar © NDC

Assumption Altar, Charles-Antoine Bridan (1772)

It is worth highlighting the remarkable work of the 18th-century vault: a round-arched design resembling a palm tree, emphasizing the power of the architecture, it was built to support the colossal weight of Charles-Antoine Bridan’s Assumption of the Virgin, placed directly above. This Carrara marble sculpture was installed in the cathedral in 1773 and weighs a total of 30 tons. The impression here is one of immense strength.

During the devastating fire of 1194, this is the place where three clerics are said to have taken refuge with the relic: the famous Veil of the Virgin, offered by Charles the Bald in 876. At that moment, only the crypt and the royal portal were spared! The cathedral burned for three days; the clerics heard the fire crackling, the beams burning, the walls collapsing. After these three days (a number with profound significance for believers), they were found alive, and the relic was miraculously saved from the flames! The clergy and the people alike were filled with enthusiasm: a tremendous wave of generosity and creativity arose to build and rebuild what would become the Gothic cathedral we know today.

Crypt: Merovingian wall © NDC

René Merlet’s research was halted in 1905 due to a lack of funds. His work uncovered a corridor in the northwest corner of the crypt. This long sloping passage likely provided access to the upper sanctuary —perhaps one of the first cathedrals, probably Merovingian.

The floor and the base of this wall are thought to be Carolingian in origin. The right-hand wall, meanwhile, was reinforced with additional supports in the 13th century, during the construction of the Gothic cathedral.

At the far end of this corridor, René Merlet discovered stone steps and uncovered several supports, including the base of a cruciform pillar. This pillar indicates a structured organization emphasizing the sanctuary. This corridor could be an access point to the Carolingian-era cathedral, providing evidence of the earliest cathedrals —since Fulbert’s was only the fourth or fifth.

The rest of the space has not yet been excavated; it very likely contains the remains of the choir and nave of the primitive sanctuaries. Christian Sapin, an archaeologist and specialist in the Early Middle Ages, points out: “Textual sources are scarce and consist mainly of mentions of key dates that may have led to total or partial reconstructions of the monument. Regarding Fulbert’s architectural work, the most important document is a manuscript reference to the reconstruction after the fire of 1020, along with a letter from Fulbert, dated approximately 1024, to William V, Duke of Aquitaine, in which he specifies that the ‘cryptas’ are completed and that he intends to cover them before winter to protect them.”

Several fires have marked the history of the cathedral: a fire is mentioned in 594; in 743, Hunald, Duke of Aquitaine, sacked the city after disputes with the son of Charles Martel. In 858, the Vikings set fire to the cathedral and pillaged the city. Two other fires are believed to have occurred in 962 and 1020.

In this Saint-Lubin vault, we find ourselves in the very depths, the maternal womb of our sanctuary. Here, one can only feel the deep roots of 1,500 years of prayer, the mystery of each individual’s relationship with God, of God’s relationship with each person, allowing oneself to be touched by its stones, its secrets, listening to the silence that nourishes and inspires hope.

These roots are magnificently evoked by Péguy in his Presentation of the Beauce to Our Lady:

“Two thousand years of toil have made of this land

An endless reservoir for the ages to come.

A thousand years of your grace have made of these labors

An endless sanctuary for the solitary soul.”

Article provided by the Welcome and Tours service of the cathedral,

as part of the millennium of the crypt.